Animated Documentary in the Post-truth era

- Travis Maxwell

- Jul 9, 2025

- 11 min read

Updated: Jul 12, 2025

Introduction: Documentary and animation history

Documentary is a nebulous term; whether one defines it like John Grierson’s “creative treatment of actuality” or believes that “there is no such thing as documentary” like Trinh T. Minh-ha, one can see the terms consistent shifts and emendations. Bill Nichols, in his book Representing Reality, proposes six modes of documentary: expository, poetic, observational, reflexive, performative, and participatory (DelGaudio, p.189; Selway; Anderson-Moore). However, classifying documentaries has become increasingly difficult with the emergence of the animated film, which attends to non-fictional subjects but does not capture any profilmic event, the “animated documentary.” A concept that may appear like an oxymoron. Nevertheless, the genre has become increasingly popular; Google has millions of searches for “animated documentary” covering varied non-fiction topics, such as journalism, forensics, games, education, and information. Furthermore, historically, animation predates film with the invention of optical toys and has tended to non-fiction subjects, like education, for over a century (Ehrlich, pp. 20-1; 189-90). Evidenced by Max and Dave Fleischer’s The Einstein Theory of Relativity (1923), which sought to illustrate complex and abstract concepts. The film blended both live-action and animation and used a proto-CGI rendering of the earth, predating the ‘Earthrise’ photograph (Popova; Lumière). Therefore, it may be unsurprising to hear that Höffler and Leutner and Berney and Betrancourt, through research, found that learning and studying using animation is more effective than static images (150-67; Kombartzky et al, p.424). Thus, one can extrapolate the benefits animation could serve not only students but the public as an educational tool. Furthermore, as early as 1910, Thomas Edison made instructional films, and according to Richard Fleischer, Randolph Bray partially animated films for the US government prior to 1916. Likewise, the Soviet Union explored animation as a tool to educate and distribute information, such as in Vsevolod Pudovkin’s The Mechanics of the Human Brain (1926). Predating this is British filmmaker Percy Smith’s How Spiders Fly (1909), which was made using stop-motion to aid people in overcoming their arachnophobia (Roe, pp. 8-9). However, despite this, Disney’s pivotal role in creating animated content has meant that animation is culturally understood as removed from reality (Ehrlich, p.21). Where this essay is concerned is in assessing the arguments for and benefits of animated documentaries, which will be illustrated by engaging academic texts and analysing Persepolis and It’s like that. This essay will also tackle the disadvantages of animated documentary in a post-truth era to determine whether animated documentary is a sufficient source of information and how the medium can avoid sensationalism and misinformation.

Documentary Animation: Methods of storytelling

Anabelle Honess Roe argues in her book Animated Documentary that animation, similarly, to live-action documentaries, presents and tackles their subject in different ways. For example, animation can function in a mimetic or “substitutive way,” meaning to compensate for something, such as events that have no captured footage and/or would be impossible to showcase otherwise. Winsor McCay’s The sinking of Lusitania (1918), widely known as the “first animated documentary,” used animation to show the sinking of the ship. In this example, animation functions akin to reconstruction in documentary, as it asks the viewer to make reasonable assumptions and allowances. Like reconstruction, it offers a reasonable interpretation of what occurred in the absence of footage (8; 22-4). The second usage of animation is non-mimetic substitution, wherein the animation does not attempt to create a visual link to reality; instead, embracing animation as a mode to express meaning through aesthetic realisation. For instance, the film Hidden (2002) is an animated interview documentary in which the soundtrack is loosely interpreted via animation. The film animates a radio interview with a young illegal immigrant but does not attempt to portray characters accurately to their real-life counterpart. Mimetic and non mimetic substitution can be regarded as creative solutions in the absence of footage, with the difference being approach, as one attempts realism and the other forgoes it, and by forgoing it, non-mimetic can imply deeper meaning through animation (24; Roe, p.26; Plomp, Forceville, p.357). The last mode of animated documentary is evocation; evocative animation serves as an answer to representing concepts like emotion, mental states, and feelings. To evoke means to call a feeling, faculty, or manifestation into being and to call up a memory. Filmmakers have historically utilised a variety of wavy lines, optical devices, blur, and colour palettes to represent mental states. Additionally, camera angles are implemented to indicate to the audience that they are seeing through a character’s point of view. However, animation is increasingly used as an alternative to represent the abstract and evoke the experimental. For example, Samantha Moore’s An Eyeful of Sound (2009) is a movie that focuses on synaesthesia, a neurological condition that combines typically separated sensations. Moore uses animation to show how people with this condition can see images alongside sound. The function of this type of animation is to evoke the reality experienced by the documentaries subject. However, mimetic, non-mimetic, and evocation animation are not mutually exclusive, as one documentary could demonstrate all three. However, understanding how and why animation is used for documentary enables us to comprehend its advantages over traditional documentary and will help with the analysis of subsequent sections (Roe, pp. 25-6; Roe, p.109).

It's Like That (2003)

It’s like that is a self-funded short film made by the Southern Ladies Animation Group (SLAG). The film is based upon the phone calls of three young children to journalist Jacqueline Arias. SLAG’s Nicole McKinnon heard the interviews on ABC’s (Australian Broadcasting Corporation) radio documentary Un-Australian Behaviour, Part 3: The Children. The radio documentary pertained to the detainment of children under Australia’s Migration Act 1958 and the introduced system in 1993 regarding the mandatory detention of asylum seekers. Members of SLAG would sift through 6 hours of audio, before identifying the three boys they would use for the short, aged 11-12 (Roe, p.90). The children would go unidentified at the request of the families, instead depicted as birds within the short documentary. The short uses multiple art styles from 13 different artists, from 2-d hand-drawn animation on paper, to flash, to 3-d digital animation and stop-motion knitted puppets. The art styles are unified by colour scheme, music, sound, and the children’s voiceover. The boys begin first, speaking of food, likes, and dislikes, before speaking on more sombre topics, their unhappiness, being separated from parents, and worries, one child stating, “I think if we stay here, we will die.” Later into the film, the children recount their arrival at Australia, a trip on a leaking boat. One child says how he seen a boat capsize after being lit on fire (Quigley; NSFA). The film works as an expose of Australian law and reveals deeper truths regarding the treatment of vulnerable refugee children (Roe, p.91) The film depicts the kids as birds in a small room with one window, making an obvious parrel between the children and caged birds. This symbolism becomes more apparent through the portrayal of free birds, flying, and their interviews which stress their desires to be free and outside the building and fences (their cage). Furthermore, the appearance of the children as soft-knitted birds, reminiscent of old-fashioned plush toys, makes them appear innocent, fragile, and at risk of being unravelled (Roe, p.90; NSFA). The film uses non-mimetic documentary in a way that evokes emotion, but moreover, in a way that traditional documentary cannot, as it inscribes deeper meaning into the depictions of the anonymous children, not achieved through merely depicting reality.

Persepolis (2007)

Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis is a Cannes award-winning film, banned in Iran for being anti-Iranian. The film is an autobiographical account of her upbringing in Iran and is the adaptation of her novel Persepolis (2000) (Roe, p.179; Chute, p.106). The story is positioned within the overthrowing of Mohammed Reza Shah and his instillation in Iran as royalty by British forces. The Shah would throw a one-hundred-million-dollar celebration for the Persian Empire’s founding 2500 years ago. However, it was arguably a thin façade, as it was more likely to celebrate his rule and mission to Westernise Iran. Furthermore, less than a decade later, he would be overthrown by a coalition of secular leftists and Islamic opponents; meanwhile, his Western allies distanced themselves, disturbed by his autocratic rule. Thus, the once-exiled Ayatollah Khomeini would arise to power and instil his theocratic regime, which persists to govern Iran today and is used to undermine and imprison Khomeini’s once-allied left. Satrapi would witness this regime shift and experience the Iraq v. Iran war before being exiled to Austria at age 14 by her family. Satrapi would later move to France and take an interest in Spiegelman’s Maus and its ability to tackle serious subjects. Inspired, she would create her own autobiographical novel, Persepolis, named after the “conceptual centre of her homeland.” The film, made in tandem with French comic artist Vincent Paronnaud, would implement an artisanal mode of production (traditional hand-made animation), as insisted upon by Satrapi. The story forgoes being a one-to-one adaptation; rather, it portrays a more chronological retelling of events but maintains the look and tone of the graphic novel (106; Prasch, pp. 80-1). The film keeps fidelity with the German expressionist and Tintin evoking visuals of the novel, using a black and white monochrome colour scheme (for the most part). Satrapi’s trademark “stylised realism” and woodcut aesthetic enable the viewer to slip into and believe in the world of Marjane while setting it apart from CGI animation, making the visuals striking and individual (Molloy, p.42; Stables, p.1; 81).

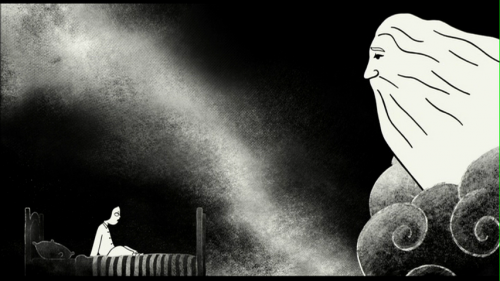

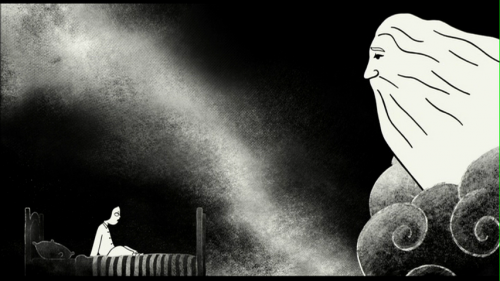

Persepolis opens to an older 30-something Marjane at Paris’s Orly airport, these scenes being in colour. Upon imagining her childhood, her 7-year-old self enters the frame in the film’s black-and-white aesthetic, and the audience is whisked away to Tehran. Persepolis’s Marjane is a girl who idolises Bruce Lee, communism, and Karl Marx, converses with God, and aspires to become a prophet. Marjane’s parents and relatives oppose the Shah’s regime. It is through Marjane that we see the religious crackdown on women’s freedoms after the revolution, the Iraq v. Iran war, death, and political zealotry from institutions. Marjane is sent to Vienna to finish school, where she discovers alternative culture, nihilism, and experiences love and heartbreak. Dejected, homeless, and having had a near-death experience, she returns to Tehran. In Tehran, she enrols in University to study art, gets married to Reza, divorces, experiences harassment, and sees death again when the religious police raid an illegal party. Thus, her mother forbids her from returning to Iran, deeming it unsafe, and thus Marjane departs for Paris, where the movie comes full circle, back in colour (Stables, p.2). The story of Persepolis is told through evocative animation, designed to illicit feelings, emotion, and mood from the audience and call upon memories from the past (Roe, p.109). Persepolis evokes feeling through a highly evocative art style. To elaborate, German expressionism covers a wide range of arts, but most notably and relative to Persepolis are the painting which directly inspired it, notable for their gestural brushstrokes, juxtaposing colours, and distorted figures. German expressionism arose in a time people became disillusioned, the promise of war loomed in Germany, and as a result, the art was profound, emotive, and would be used to portray ideas, rather than the reality experienced (Meyer). Similarly, the art in Persepolis is brooding, emotive, and powerful, used to a similar affect, for example, in an abstract and introspective scene, we see her anger directed at her own manifestation of God. Whom she blames for “doing nothing.” Marjane questions her own beliefs and faith in God, adding “quiet, I never want to see you again,” repeating “go away.” The scene occurs in a liminal space, wherein Marjane is sat on her bed, pictured as small against the background, emphasising the feeling and tone of powerlessness. The scene evokes emotion from the audience as the themes of loss, powerlessness, grief, and the questioning of one’s own beliefs is relatable to many people, while also deeply personal, as it showcases the mental state of the character (Persepolis, 21:45-22:02).

Additionally, non-mimetic animation is used within the film. Specifically, within the scene with the Shah, who is illustrated as a puppet. In a fairytale-esk story told by Marjane’s dad, we see the Shah’s father described as a man who became emperor through Britain, by giving them oil. Thus, the allegory becomes clear. The Shah and his father are shown as puppets in a puppet show with befitting cardboard-esk backgrounds, and stilted puppet-like movements. Thus, the allegory becomes clear. The puppet visuals symbolising the Shah’s place as a puppet government. The non-mimetic asserted through this break in animation style and focus on artistic representation (Persepolis, 06:00-07:35).

Animation in the Post-truth era

In Nea Erlich’s Conflicting realisms: animated documentaries in the post-truth era, she tackles the representation of school shootings and war within animation and indicates a hidden hierarchy. To elaborate, Keith Maitland’s award-winning film Tower (2016), a film covering America’s first school shooting, Maitland in an interview speaks of his unease in animating tragedy, stating “… I want to make a movie about the worst thing that ever happened to you 50 years ago, and it’s going to be a cartoon. Let’s talk!” Through this, we can clearly see that despite the excess of animated documentaries, animation has a reputation as being fictional, light-hearted, and childish. Further, the recent surge of animation’s usage in non-fiction signifies a shift within modern visual culture. Animation is omnipresent in everyday life, in public, and on technological devices, ergo making people accustomed to seeing it represent real events and emotions. Animation is increasingly important in knowledge production but serves to challenge traditional boundaries between fiction and non-fiction. Erlich further argues that the truth claims of documentary in an era of post-truth characterised by the blur in fact and fiction are replaced with ‘truthiness,’ wherein the truth value of a non-fiction work is based upon the viewers desire for something to be true, rather than facts or concepts which are known to be true (20-3). Tom Gunning’s concept of ‘truthiness’ states what feels real does so because it aligns itself with our preconceived notions of the world. Through reaffirming the beliefs of the viewer and appearing transparent, it can be misleading, and deceitful. Whereby, animation’s overt constructedness, paradoxically, may render it as more realistic, able to disrupt conventions and prevent complacent viewing, as such theorists, like Anabelle Honess Roe have pointed to it as more authentic approach to documentary (27). Roe also argues that animation freeing itself from the indexical bind of documentary is its liberating strength. As, through severing the casual connection between the filmic and profilmic, one can bring things “temporally, spatially, and psychologically distant from the viewer into closer proximity.” Thus, enabling the filmmaker to show things which were not recorded or depict abstract things like mental illnesses or thoughts through mimetic, non-mimetic, and evocative animation. However, Plomp and Forceville contest, that while the multiplicity of styles, techniques, and means of production create visual excess which may enhance metaphors and rhetorical points, it can devolve into sensationalism. Animated documentaries lean towards the creative treatment of documentary. Regardless of whether it is animation or live action, the more creative a documentary is, the more it risks being fiction, thereby spreading misinformation, these themes will be explored further in the subsequent concluding section (357-8).

Conclusion

As discussed, in the post-truth era of media, fiction and non-fiction has been blurred, with the truth claims of documentary being called into question and replaced with “truthiness.” The creative treatment of documentaries may derail facts, as such non-fiction filmmakers must adhere to the standards of research, exposition, and argument within the documentary genre. However, non-fiction filmmakers can be creative, so long as it does not promote misinformation, which is what can happen, when one takes too many creative liberties for artistic expression. However, animated documentaries can disrupt conventions, inscribe meaning, and can prove an invaluable method for representing reality, in both “real” and unreal ways as shown in this essay (Plomp, Forceville, p.358).

Figures

Bibliography

Anderson-Moore, Oakly. Nichols’ 6 Modes of Documentary Might Expand Your Storytelling Strategies. 17 9 2015. Website. 13 1 2024.

Anniek Plomp, Charles Forceville. “Evaluating animentary’s potential as a rhetorical genre.” Visual Communication (2021): 357-8. Online Journal. Burns, Ken. Film Documentary Guide: 6 Types of Documentaries. 7 6 2021. Website. 12 1 2024.

Chute, Hillary. “The Texture of Retracing in Marjane Satrapi's "Persepolis".” Women's Studies Quarterly (2008): 106. Online Journal.

DelGaudio, Sybil. “If Truth Be Told, Can 'Toons Tell It? Documentary and Animation.” Film History (1997): 189-90. Online Journal.

Ehrlich, Nea. “Conflicting realisms: animated documentaries inthe post-truth era.” STUDIES IN DOCUMENTARY FILM (2021): 20-3. Online Journal.

—. “Conflicting realisms: animated documentaries inthe post-truth era.” STUDIES IN DOCUMENTARY FILM (2021): 27. Online Journal. Lumière, Frère. Einstein The Theory of Relativity, 1923,

Dave and Max Fleischer. 31 10 2022. Website. 12 1 2024.

Meyer, Isabelle. German Expressionism - One of the Greatest German Art Movements. 15 2 2021. Website. 14 1 2024.

Molloy, Duncan. “Film & DVD Reviews.” Film Ireland (2008): 42. Online Journal.

NSFA. IT'S LIKE THAT. 2003. Website. 2024 1 14.

Persepolis. Dir. Vincent Paronnaud Marjane Satrapi. Perf. Gena Rowlands, Sean Penn, Iggy Pop, Mathilde Merlot Amethyste Frezignac. 2007. Animated Documentary. Popova, Maria. Einstein’s Theory of Relativity, Explained in a Pioneering 1923 Silent Film. 11 6 2018. Website. 11 1 2023.

Prasch, Tom. “Persepolis (2007).” Film & History (n.d.): 80-1. Online Journal.

Quigley, Dr Marian. It’s Like That. 2003. Website. 15 1 2024.

Roe, Anabelle Honess. “Introduction: Animation and Documentary's shared history.” Introduction, Animated. Animated Documentary. London, Hempshire, New York: Palgrave Macmilan, 2013. 8-9. Ebook.

—. “Animated Interviews: Absence as representational strategy.”

—. Animated Documentary. London, Hempshire, New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2013. 90-1. Ebook.

Comments